[ad_1]

Evan Kleiman talks with Francis Lam at The Splendid Table about food, restaurants, radio, and friendship. This interview originally aired on The Splendid Table and has been edited for length and clarity.

Italy: “It felt like a place that I belonged.”

The Splendid Table: I once heard you tell the story about when you were traveling in Italy for the first time as a teenager, and I think this probably was in the late 60s, or maybe early 70s. You heard two men talking about food on the train.

Evan Kleiman: It was 1970. I was 17 years-old. I graduated really early from high school, and so I took a break. I had been working through school, starting in junior high, so I had money saved, and I went to Europe. I had a first-class Eurail pass – a present that my mom gave me as a gift for my trip.

I was in this train compartment with these men traveling in northern Italy. They were in beautiful suits, with briefcases. And because of my French, I could understand enough of what they were saying to get it. I had never heard grown men talk about what they had eaten and what they were about to eat. I felt that the culture had some place for me. And why I was teed up to key into that was because I was just a total besotted food nerd always. It was my way to understand the world, and people who sometimes made me feel really uncomfortable.

Food was something that I just love to make, obviously, and eat. But I also read about food, too. I was starting to read about food when I was nine, or 10. There was no internet. So I read cookbooks that were interesting. I read headnote introductions to cookbooks. I was just a voracious compiler of weird food stuff.

I think for a young person that was probably pretty unusual, even in Los Angeles.

I was considered to be a weirdo. When I went to high school reunions, my fellow students said that they knew I would be involved with food in some way. I always asked my mom’s friends if they had any old gourmet magazines they would give me, and I remember one year around Passover, I found this recipe for matzo balls that had chopped parsley and nutmeg in them. And so I convinced my mother that she should let me make them that year. And she accused me of being a heretic.

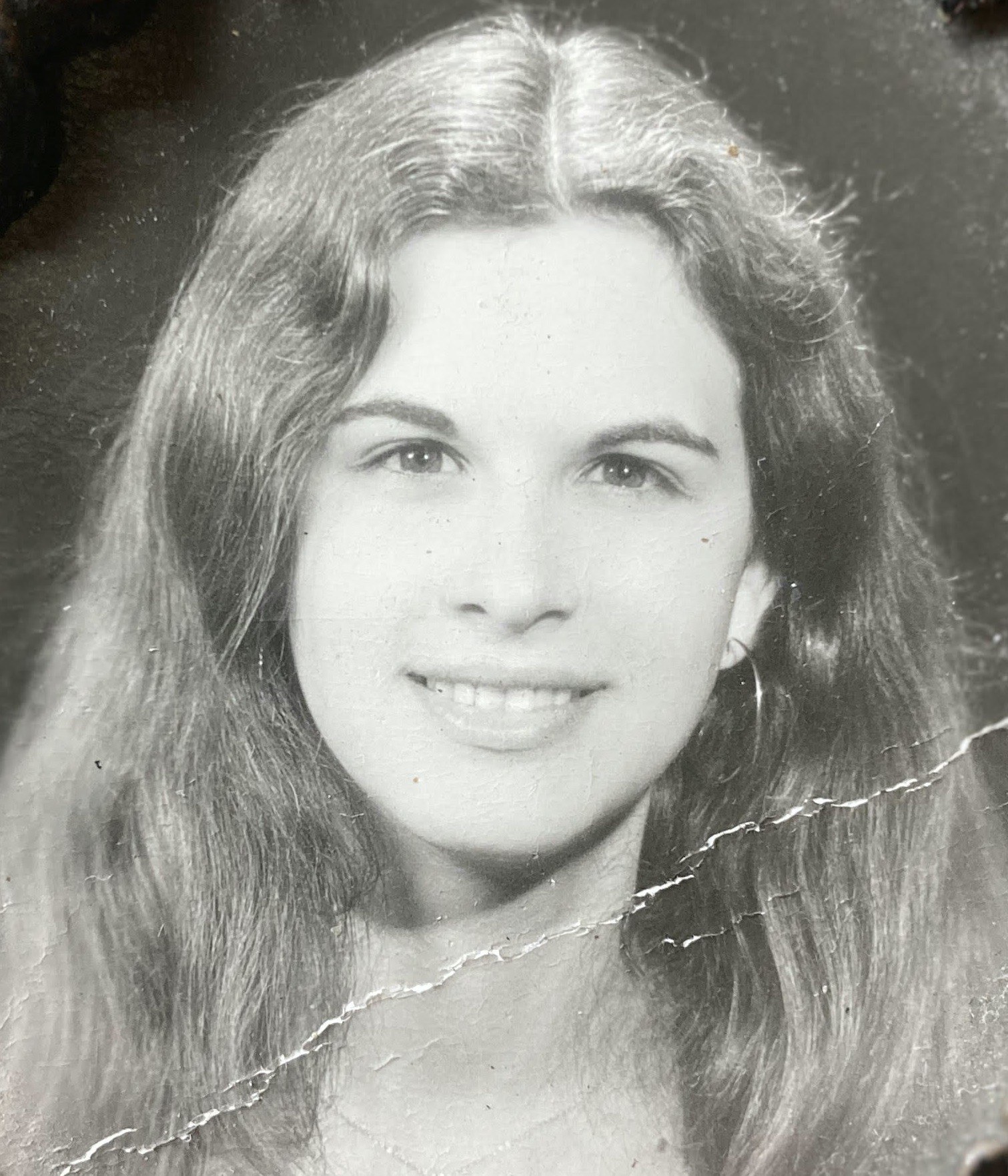

“My ID photo. 18 yrs old, Università dei Stranieri di Perugia, University for Foreigners of Perugia.” Photo Courtesy of Evan Kleiman.

How did you get to Italy?

I was going to France; and I had been a French major in high school. So I went to France, and it pretty much just immediately spit me out. I was a super shy kid traveling. I was by myself. I was walking around as a stranger as a tourist. They weren’t patient with my imperfect French.

I came to Italy because I ended up hitchhiking all through Yugoslavia and Greece. I lived in Greece for a while, and then ended up going back to Italy. It felt like a place that I belonged. I don’t know how that happens, how your soul feels like it belongs to a place.

This was a life-changing experience for you.

Every part of that Italian experience was just so engaging for me. It was the time when in trains, you could roll down the windows completely. And so when you would pull into a station, there would be vendors there with baskets, like actual baskets made of natural materials, selling sandwiches. So even getting a rosetta, these northern Italian hard rolls that are almost completely empty on the inside filled with maybe two slices of the thinnest mortadella ever was like a peak experience.

You stayed with families, and you’d said that’s where your apprenticeship in cooking Italian food began.

I was an only-child of a single parent in LA and I didn’t grow up with any grandparents around me. So I think when I went to Italy, it’s like I found these families, even if they lasted briefly. It was in the day where you would stay in a bed and breakfast, not an AirBnB. And this is post-war Italy, still before Italy really became an industrialized nation. So things were transitioning from the grinding poverty of the post-war years, and they were still pretty difficult. If you wanted to take a shower, you had to make an appointment and pay extra. So they would turn on the tiny little hot water heater that was immediately above the shower. And you would just be there with this family sometimes sleeping in the same bedroom as one of the family members. And I was so constantly shy. I would spend a lot of time with the family helping the mom, or the grandmother, or whoever was cooking, and it was a way to feel comfortable and centered because cooking always made me feel that way. Later when I was going to school in Perugia, while my fellow American students were partying at the disco, I cooked.

You were fearful of going out and exploring, but you would feel safe in these homes?

My shyness was really considerable. I had to force myself to do everything. And I think what I loved about those years was how I saw that even though the food was incredibly simple it, could be so completely delicious. And that even in a city, everybody seemed to have links to wherever these things were made. Growing up in Los Angeles, you knew about orange groves, but it wasn’t like you felt that the farm was really close to you in any major way.

And as wonderful as Southern California citrus is, oranges a diet do not make.

You could go to Knott’s Berry Farm. And at that time, there actually were farms there. But it wasn’t the same thing as a place where every family had olive oil from a cousin or an aunt or or a sibling. There weren’t any supermarkets in Italy yet. So all of the markets that were were tiny or fresh markets in piazzas.

Are there dishes you learned to make at that time that you still make?

Spaghetti alla checca, with chopped tomatoes, with fresh basil that is set to marinate with olive oil and salt. And then right before the pasta is ready, you cut up some mozzarella and throw that in and then toss that which is room temperature over pasta, spaghetti aglio e olio, too. The soups like pasta e fagioli, ribollita, and pappa al pomodoro, minestrone. Just regular regional homey dishes.

Evan Kleiman on working with food critic Jonathan Gold: “Who knew that would become this 20-year-long relationship where I had a standing meeting with Jonathan Gold to talk to him about food. That will forever be a highlight of my personal and professional life.” Courtesy of Evan Kleiman.

Learning to cook from the locals

Tell me about your time at UCLA.

I ended up majoring in Italian literature and film at UCLA. And during the whole period of my college years, I was getting these niche grants from organizations that would pay for me to go to Italy and do a project. I would spend the whole summer there. That’s when I really started feel comfortable to seek women out to teach me. Like the portiera (concierge) of a friend’s apartment building in Milan was famous for her ravioli stuffed with potato and parmesan sauced with an amazing ragu. She then sauced the potato ravioli with the gravy – the tomato gravy from braising the meat and saved the meat for the second course. And then the women home cooks I met were kind of taken aback that I would ask to learn to cook that they almost never said, “No.”

Food wasn’t something that people honed in on as a subject of conversation and cultural intrigue and cultural cachet.

Also the fact that I was so young, I think it probably was pretty charming and flattering for them. I have to say that it wasn’t just Italy. In those early years, in my teen years, when I was traveling in Greece, where, obviously, I didn’t speak Greek, and so you would just walk into a kitchen and look at what they had and point to things. And that’s when I learned how to make those amazing Greek green beans, which are like almost as much olive oil as beans, and they’re braised forever with onions and a little bit of tomato. It’s where I fell hard for yogurt.

It’s also the first time I learned that a type of ammonia was used as a leavening agent. I went into a village bakery one day and saw something right out of the oven. And I said, “Well, I want one of those.” And he says, “You can’t have one yet.” And I didn’t understand why. And then he let me smell it. And it was like somebody putting smelling salts under my nose.

Evan Kleiman made pizza in the 1990s at her restaurant, Angeli Caffe. “Angeli was such a loving environment for children. My waiters just loved them. And we let every kid make their own pizza. It was a special place.” Photo courtesy of Evan Kleiman.

Opening Angeli Caffe in 1984: “A weird little hipster cafe”

In LA, you’re working in film, but you found your way into cooking. And eventually you open the first of your three restaurants, Angeli Caffe.

I had been cooking for money by then, for close to 15 years, because I was always expected to support myself as soon as I could. And so I started catering when I was like 15 or 16. I worked for a Hollywood caterer starting when I was in high school, and all throughout college. And so it was very strange because I was so programmed to go to college, get a degree, get a job that had somehow related somewhat to my degree. But my degree was in Italian literature and film. It’s funny how that major did end up being useful in my restaurant life.

But before that happened, I did get a job working for an independent producer, working with writers and being a reader. But I was still catering. At night, I would come home from work and I would still cook on my tiny little apartment-sized stove. And I realized at some point that I just really loved cooking more than anything, but I needed to get a job in a restaurant. So at that period of time, there was a restaurant in LA called Mangia, I would say it was the first real Tuscan restaurant in LA. It showed a completely different way of eating Italian food than most of what you saw at that time. I went in and I told the owner that I knew how to make the food. And I offered to work for her for a couple of weeks for free, and then she could hire me, which is what happened, and I worked there for maybe a year or so. Restaurant life felt like a suit that fit perfectly to me. Then I was the opening chef for another restaurant that opened in LA. And finally I opened my own place. I was 31. I was also still shy, and I had to ask every single person I ever met for money to open the place.

Evan Kleiman remembers the food she loved at her restaurant Angeli, especially the homemade bread. Photo courtesy of Evan Kleiman.

How would you describe your restaurant Angeli?

I hope I don’t start crying. It was probably the first casual cafe in LA where the decoration wasn’t red booths, and red-and-white check tablecloths. I was very good friends with an architect named Thom Mayne because he had been going out with one of my roommates at UCLA. Thom was part of a seminal deconstructivist architecture firm of the 80s called Morphosis, he has gone on to win a Pritzker Prize and is immensely famous. He designed my 1000-square-foot, tiny, little place on Melrose. We opened and people were standing in line for two hours to eat sandwiches and antipasti because we didn’t even make pasta at the beginning. I knew that I wanted to bring the menu in gradually, so I wasn’t overwhelmed. So it was this weird little hipster cafe.

I know more than one person that credits you with inventing the caprese salad.

I just think that’s ridiculous. I don’t believe that. I don’t know, I think that what I did was come up with a menu that, to me, was just basically copying menus from what I experienced in very humble places where I ate in Italy in the 70s. And then that kind of menu became like a template for the deluge of Italian casual that happened.

I think that’s meaningful because if you didn’t invent the caprese salad, didn’t you invent the idea of it?

No, and I didn’t invent spaghetti aglio olio or all the other things that were on the menu, but I think it was maybe the first time that they were just put together in a way that made them super attractive to a large number of people.

Which is a very modest way of saying you popularized these dishes that are totally ubiquitous now. And not just the dishes, but elements of Italian culture that Americans weren’t tuned into yet. And I’ve heard you say that for you, the restaurant scene was an educational enterprise. You would quiz your waiters.

They had to study. There was no bruschetta with a ‘shh’ sound at Angeli. I had been an Italian major, I couldn’t have people working for me mispronouncing Italian words, or have misspelled words on the menu. Because at that time, most Italian restaurants that were getting press were Northern Italian restaurants, and they were doing rich food, and a lot of sauces. And it was like the opposite of what I was doing. The staff needed to be able to explain the context to people who would order a spaghetti aglio olio. And it would come and it would just be a bowl of spaghetti with olive oil and garlic, and sometimes the diners just didn’t get it.

“In 1985 we expanded to double the size of the restaurant. This photo of the construction site was taken by a friend, director of photography Michael Chapman (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull etc). It expresses my interests in art, photography, a 1960s Italian aesthetic and why Angeli was so different. That mash up of traditional food with a different aesthetic. My biz partner at the time John Strobel is at the bar and Albert Solís (one of our original waiters who went on to open Mexica in Los Feliz is sitting with me at the table.” Photo courtesy of Evan Kleiman.

How did the restaurant change through the years?

The restaurant morphed because guests took ownership of the space. And so it started out as this sort of cutting-edge hipster cafe in 1984. And in 2012, when I closed it, it was this hilarious place where at one table, you would have people who lived in the neighborhood in their sweatpants like in pandemic garb, let’s say eating there four times a week, it was basically their kitchen. It was like a low-key place for actors, producers, or people in the movie business, sitting next to a young couple all dressed up going out for their first date or even getting engaged. And because by that time , I had an entire generation of kids who grew up there.

I was thinking about what I miss the most about not having Angeli and it’s when I meet children who are eight-to-10 years old. And I think how sad that they never got to experience Angeli because it was such a loving environment for children. My waiters just loved them. And we let every kid make their own pizza or bread. It was a special place.

Good Food host Evan Kleiman and producer Jennifer Ferro worked together to make the show come to life. Kleiman says that Ferro introduced her to her friend and colleague, food critic Jonathan Gold. Photo courtesy of Evan Kleiman.

The side hustle: Good Food on KCRW

In 1997, you took over as the host of a radio show Good Food on KCRW.

I wasn’t the one who pitched the show. The show was pitched and originally hosted by Mary Sue Milliken and Susan Feniger who had burst onto the burgeoning television food scene as the “Two Hot Tamales.” As fellow female chefs in the early 80s, we had restaurants on the same street. And so they pitched this idea to KCRW. And then after they’d done it for about a year, they stepped back. And I had been a guest on the show a few times. And so the producer, Jennifer Ferro, who is now president at KCRW, asked me if I would do it.

You have a segment on Good Food called The Market Report. You have someone actually walking in the Farmers Market talking to farmers.

That grew out of the fact that in those days, so many chefs were just completely inarticulate. It was interesting. I would interview a chef, and they just couldn’t talk, which I understood having been a shy chef. We discovered that by interviewing a chef at the farmers market along with a farmer, it became like more of a safe place for them in a way.

Evan Kleiman on friend Jonathan Gold: “He really pushed me to look at food with a different vocabulary.” Photo courtesy of Evan Kleiman.

One reason why I’ve always loved listening to your show is because you have such a wide ranging interest. Talk about some of your favorite interviews.

I loved getting to interview nearly all of my culinary aunties, the women whose books that formed my palate and taught me so much in my early teens and twenties. For example, Claudia Roden and Marcella Hazan. The first interview I did with Marcella was really personal, moving and amazing. She and Victor ended up coming to Angeli a couple of times. She ate my Italian style well – cooked green beans, and she told me I was incredibly brave for making them that way in a restaurant setting in California. And, Paula Wolfert. And of course, Julia herself, I interviewed a couple times on her own, but especially with Jacques. I mean, those early interviews were shocking when they started writing books together. They were just lovely.

What I really loved was when Jennifer Ferro, my producer, got the idea to bring Jonathan Gold from the LA Times in every week for an on air interview about his review that week. Who knew that would become this 20-year-long relationship where I had a standing meeting each week with Jonathan Gold to talk to him about food. That will forever be a highlight of my personal and professional life.

Jonathan Gould is probably the greatest restaurant critic who’s ever worked in America.

He really pushed me to look at food with a different vocabulary. That was something pretty great.

[ad_2]

Source link

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62810996/Amm_DeepSentinel_01.0.jpg)

More Stories

TheyDo fires the starting gun on the race to own the customer journey • TechCrunch

How To Develop Buyer Personas: A Crash Course

stocks to buy: 2 top stock recommendations from Aditya Agarwala